Materialists review: Are Chris Evans, Dakota Johnson, and Pedro Pascal perfectly miscast?

Materialists, Celine Song's highly anticipated follow-up to her critically heralded debut feature Past Lives, may be too clever for its own good.

On paper, Materialists is perfection. It's a love triangle romantic comedy, headlined by three movie stars with which the Internet is absolutely obsessed: Chris Evans, Dakota Johnson, and Pedro Pascal.

The plot feels like something out of a Golden Age Hollywood movie. A cynical career girl (Johnson) in New York City plays matchmaker to the rich and shallow. But when she meets a suave, handsome, and outlandishly wealthy man of her own (Pascal), will she choose him? Or will her heart lead her to the struggling artist (Evans) with no savings, no prospects, and only annoying roommates and a cater-waiter gig to his name?

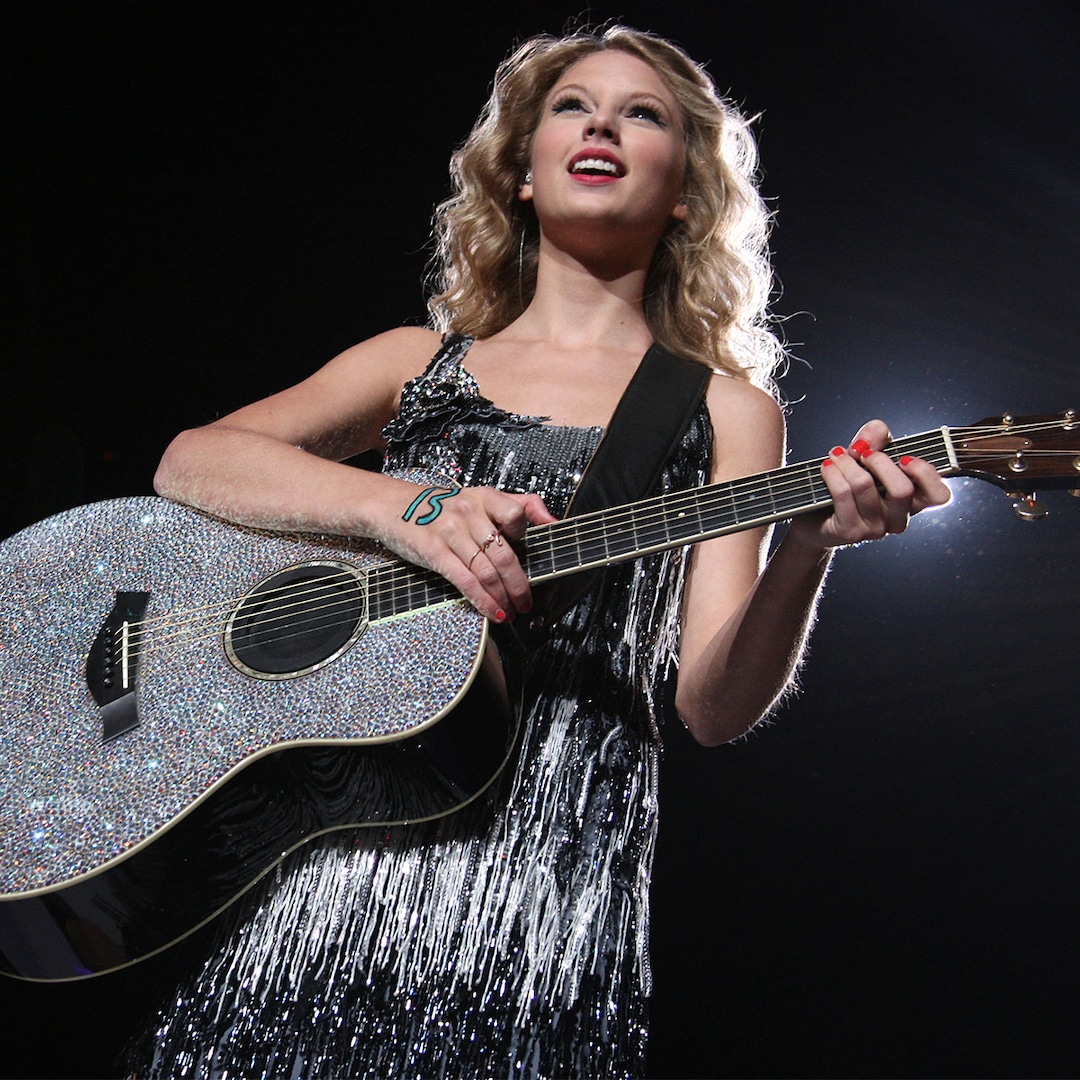

Such a humorous heroine role used to go to the likes of Jane Russell (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), Lauren Bacall (How to Marry a Millionaire), or Katharine Hepburn (The Philadelphia Story). In the '90s revitalization of rom-coms, you might have seen Meg Ryan or Julia Roberts in such a part. Though she has done romantic dramas (Fifty Shades of Grey) and comedies (How to Be Single), casting Dakota Johnson now in such a role is a spiky choice.

It's not that Johnson doesn't have the range to play the hard-nosed career girl who might, at her core, be a hopeless romantic. However, her public persona is one of a snarky cynic, who refuses to take anything Hollywood too seriously. And this attitude has been embraced by Materialists' beguiling promotional campaign, which flaunts her and co-stars Evans and Pascal's chaotic chemistry. Yet her attempt at earnest romanticism in the movie itself hits shallow at best because of this persona — and similar problems afflict her co-stars as well.

While the actors in these lead roles might be performing them well, their personas are so big beyond the movie that they overshadow what Song is attempting to do with Materialists. Let's break it down.

Dakota Johnson is not believable as a girl who has ever been broke.

As Lucy M., Johnson is the kind of sleek sophisticated Manhattanite that Sex and the City fans aspire to be. Like Carrie Bradshaw, Lucy can wax poetically with a broad smile to sell the concept of perfect love and great sex to her hungry clientele. But she's not a true believer like Carrie. When she speaks with her coworkers, it's all about numbers: height, salary, and BMI.

When she lectures coolly on matters of matchmaking, it's as if she's talking about interlocking puzzle pieces that just need to fit. Talk of actual love is shunted to the side as inconvenient, which is reflective of Lucy's background. Nine years before, she was an aspiring actress with no rich parents to supplement her ambitions. Like many a romantic heroine (reaching back to Jane Austen), Lucy doesn't want to end up poor. To her, being poor guarantees being unhappy, because she's been both. So a future with John (Evans), who is still pursuing his dream of acting all these years after they broke up, seems a foolish move.

In a telling flashback, Johnson throws herself into a public argument over money, but her desperation feels like a performance. The sight of her wide eyes drinking in the lavish gifts of her millionaire boyfriend is funny, but likewise it also feels false because of what we know of Johnson herself. Her persona is one of no-bullshit, fueled by the glimmering privilege of being born into a wealthy and very famous Hollywood family. Her sophisticated, surly attitude toward movie press for years has bolstered this persona, along with her pushback on daytime TV's former queen of nice, Ellen DeGeneres. Here, this persona works against her.

In this movie, though she wears less chic clothing than a movie star might on a nighttime talk show, she is very recognizable as sleek and meticulously groomed Dakota Johnson, queen of fuck-you money and its accompanying attitude. So even if she dons an off-the-rack sundress, it just doesn't feel real with a haircut that costs more than John's rent.

Casting Chris Evans as a struggling actor challenges suspension of disbelief to its breaking point.

It might have helped if Johnson had the kind of chemistry in the film that she and her co-stars share on their promotional tour, which has been full of cheeky videos of reciting lines from famous romances and challenging each other to trivia or light-hearted questions. However, Lucy has such a devoted distance to the idea of love that even when she's falling, it's hard to feel it from her.

This is further frustrating, because both of her options are dazzling. John, played by Evans, is a pretty familiar figure in New York City. A struggling actor who's taking survival jobs in waitering gigs, he has a mischievous smile and a worldweary stare. Evans uses this to express the willpower and sheer exhaustion of daring to be a dreamer in a city that has no patience for the poor.

Choosing John is meant to seem like a risk, because he can't promise Lucy financial security. It's a cliché that most couples fight about money, but it's a cliché for a reason. And yet it's hard to think of choosing John as a leap of faith when Song cast one of the world's biggest movie stars to play the struggling actor. It's impossible to look at Chris Evans' face, even bulked down from his MCU days and covered by an inviting sheen of scruffy facial hair, and not think that John's gonna make it. Even if Evans convincingly plays the role of working-class actor, such glossy optimism fights the realistic tone of what Song is doing with this movie.

Pedro Pascal is perhaps too charming for the will-they-won't-they to work.

Pascal plays Harry, a hedge fund manager who takes Lucy to astonishingly expensive restaurants, and then his jaw-droppingly luxurious apartment. (With a $12 million price tag!) He's a gentleman. He's tall, dark, handsome, and generous, or as Lucy puts it “a unicorn.” The catch is that while he is a rational choice for what Lucy says she wants, she fears that neither of them are really in love with each other as much as they think they could be good partners. To choose Harry would be a business decision.

What's fascinating about Materialists is that the casting of Pascal might seem intended to cover up some sort of horrible secret that Harry is hiding. (For evidence of this, just see how fans of The Last of Us will excuse all of Joel's crimes because of just how much they fawn over Pascal). That to choose him would be, White Lotus-style, a kind of complicity. Thankfully, Song doesn't take such an easy out in structuring her conflict. Harry is not a bad guy. He just might not be the right guy. But to be perfectly frank, when the whole world is deeply, deeply obsessed with Pedro Pascal, it is a wild choice to cast him as the guy we're supposed to root against when it comes to getting the girl.

Don't mistake me, I deeply admire what Song is doing with this movie. She sets up a traditional rom-com in scenario and characters, but then rejects the buzzy optimism and whimsy of standard Hollywood romantic comedies to create something cuttingly modern.

The tone of this comedy is not broad. The banter is not bouncy. Instead, Song commits to an earnest indie understanding of love and relationships. Her characters are not necessarily looking for love as much as they are fleeing from loneliness. Desperation mixes with hope, cynicism with rationale. New York City is not a heaven of designer shoes and an endless supply of eligible bachelors. As John shows, it is a place of bustling bodegas, grimy street corners, hole-in-the-wall theaters, and embarrassing squabbles that interrupt Times Square traffic.

Through all the film's conversations about money, the undercurrent is about worth. What do we think we are worth, and what will we risk to be with someone who really sees that? In that, Materialists is a deeply romantic film. Rather than opening with a typically glossy Manhattan rom-com montage, Materialists opens with a strange scene, where a caveman and cavewoman exchange gifts and bind themselves together with a ring made of a small flower.

This suggests that marriage has always been about what we can offer each other in a relationship. Song bolsters the sincerity over Hollywood romanticism by choosing a color palette that's less vivid than those of the '90s rom-com heyday. Likewise, a subplot about one of Lucy's clients going on a truly heinous date risks derailing the film's potential feel-good energy. There's a sense that Song is making a romance comedy for cynics. And in an online dating scene that seems increasingly bleak, with people lying on their profiles or gaming the system by choosing sexual inclinations that don't actually appeal to them or even dating AI in lieu of other humans, perhaps we've all become cynics.

Others may be able to watch Materialists and divorce themselves from the immense and immensely charming personas of the cast. For me, I struggled to feel the movie as it truly is, as opposed to the movie the marketing campaign with its flashy stars had me expecting it to be. I suspect years from now, I'll rewatch this movie and think more kindly of it. For now, I admire that it's a big swing, with big stars, who might be, despite their incredible charm and sincere performances, its biggest flaw. For as grounded and real as Materialists aims to be, it's hard to overlook its big, shining stars to see that gritty authenticity.

In the end, Materialists feels like it's trying to check all the boxes of a rom-com, much like Lucy's clients aim to check the boxes of what they think they want. But Song wants to give us what we need. And as much as I wish she pulled that off, I was left cold.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

.png?Expires=1838763821&Key-Pair-Id=K2ZIVPTIP2VGHC&Signature=IO0~CT3pU-TcxGc~yoZSmoQx23MZVuK-~4jSii~NKEblRmyO3el7NXPu~Rh1o23voASg7hlcHLw4kvQuDK1jssEhcjoNBBvEpZ~GGOAU6yosBhpHpeF179F~h7i6VxmsBNh9gtTutkoqY73O2YCFey~IAqSzKbBqETP1kP9cAg1916Z1YkJJs-5MliMrkZ5d7-mWGLbpHp2wGj2VlMph8XzYlL4~y1O7fB~JdIS~Rs4RMRs2x0WT1qUIpHAsf3GdwtOyAmKFSpIg8xCyNGZZ5h~13nXlmpd7uPvW8tBfttpG9pFTqcway-uch5WyfHOEfi7UlJCOWrr6fCYY5PMgSg__)